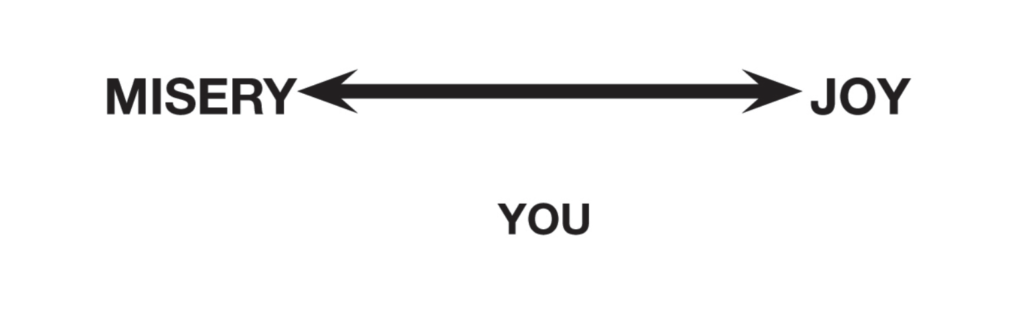

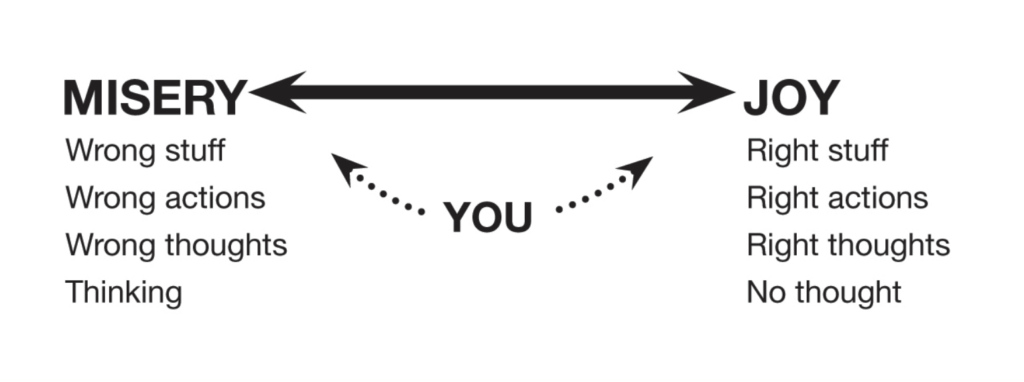

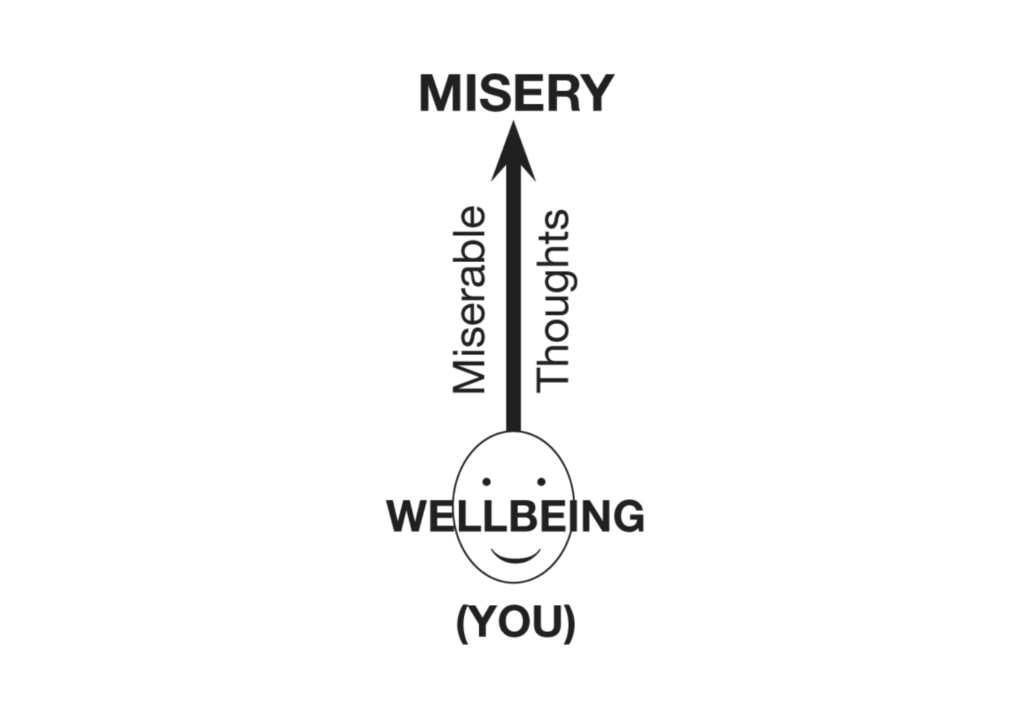

People often live as though their experience of life takes place on a continuum ranging from misery to joy.

The game of life then becomes about figuring out how to spend more time at the happy end of the continuum and less time at the miserable end.

At one level of consciousness, this path toward greater happiness seems to be marked by having the right stuff—plenty of money, a good job, a great relationship, and a nice home. But we also recognize that there are any number of people who have all those things but are still pretty miserable inside themselves. So we begin to look more deeply and conclude that it’s not our stuff but our actions that make us happy or unhappy. Do the right thing and you feel good about yourself; do the wrong thing and your conscience will haunt you until the end of time.

The problem with this is that most of us have noticed that as often as not, good things happen to bad people, and bad things happen to good people. And although we may think that “doing the right thing” should be its own reward, life viewed from this level doesn’t seem remotely fair.

It’s thoughts like this that lead us in a more internal direction in our pursuit of happiness and well-being, and we often conclude that it’s not what happens but what they think about what happens that determines our experience. So we begin experimenting with things like affirmations and positive thinking, sure that if we could just control the flow of thoughts through our own brains, we’d have the key to lifelong happiness.

A lot of people get stuck at this level of understanding because of one simple, innocent misunderstanding—they attribute their inability to think only positive thoughts to a lack of skill or effort on their part instead of recognizing that the theory itself is based on an incorrect premise: the idea that you can actually control which thoughts come into your head.

Take a minute to notice all the thoughts that come into your head. I’ll wait…

(For me, I noticed:

- Rabbits

- Sports cars

- Liniment oil

- Baseball

- The relative merits of killing a fly buzzing around my head

- Sex, quickly followed by the thought that I can’t mention that because it’s such a cliché

- Rabbits again]

Now I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I didn’t choose any of those thoughts. Which is what brings us to what seems like a real sticking point. As one of my clients once put it, “If happiness doesn’t come from what I have or what I do, and I can’t choose my thoughts, doesn’t that leave me kind of screwed?”

That’s certainly the conclusion some people come to. They decide that happiness is completely outside their control, and they give up on the pursuit. Often they actually begin to feel better when they stop trying so hard to be happy, leading them to another false conclusion: that happiness is something which can only be pursued indirectly. (The reason why that’s a false conclusion is because it’s based on the notion that happiness is a “thing”—something we can have or not have, pursue directly or indirectly, successfully get, or, if we’re not careful, lose.)

Some people, in their pursuit of connection and well-being—or as we’re calling it, “happiness”—decide that since they can’t control which thoughts come into their heads, the thing to do is to try to stop thinking altogether. For reasons you’ll understand in a few minutes, this seems to work, leading them into a complex set of routines, prayer, meditation practices, and a variety of other disciplines all designed to at least temporarily stop thought. Since feelings of peace and well-being often follow these practices, the practices themselves appear to be the means to a happy end. But the problem with all of them is that they take practice—and while that may seem a small price to pay for such a precious jewel, the vast majority of people are unwilling or unable to put in 20 years of daily meditation for 20 minutes of daily bliss.

So let’s take another look at our fundamental premise:

The one thing inherent in all these notions is the idea that misery and joy are somehow things that are outside us, and that we need to do things (or stop doing things) in order to get them. But here’s another way of looking at it, one that stands our usual notions of where to go to find well-being on their head:

A quick look into a baby’s eyes will reveal that we’re born at peace—in tune with the infinite, in touch with our bliss, resting in the well of our being. But even when we’re babies, our very human needs from time to time interfere with our connection to this innate well-being. We experience physical discomfort, and because we don’t yet understand the source of that discomfort, we do the best we know how to do—we scream bloody murder! Then, to our delight and amazement, someone comes and “makes it better”—they feed our hunger, dry our bottoms, entertain our nascent brains with funny noises and roller-coaster-type movements . . . and before we know it, we’re nestled back into the bosom of our innate well-being.

Over time, it’s the most natural thing in the world for us to begin to connect and even attribute that return to well-being to the people or activities that seem to be causing it—we’re okay because Mommy loves us; we’re okay because Daddy protects us; we’re okay because the people around us, for the most part, appear to have our well-being at heart. And then one day we do something in our joy that Mommy or Daddy doesn’t like—we splash paint on a wall or cry when Daddy is tired—and suddenly the ocean of love we’re used to swimming in is filled with sharks and other monsters too horrible to mention. Before long, we’ve bought into the myth that love and well-being exist outside us, and the need for a persona is born.

But well-being—happiness, connection, love, peace, spirit—is our essential nature. So all our attempts to capture these feelings from out in the world, no matter how well intended and practically followed, are doomed to fail. Not because happiness and well-being are unattainable, but simply because it’s impossible to find what has never been lost.

This leads us to our second secret:

Well-being is not the fruit of something you do; it’s the essence of who you are. There is nothing you need to change, do, be, or have in order to be happy.Click To Tweet

The reason why this understanding of the source of well-being is so significant is that so much of our energy and time is squandered in pursuing goals and projects and financial incentives and relationships that we believe will “make” us happy. And so much of the stress and strain we experience in our lives is brought on by our misguided attempt to make ourselves feel better by having, doing, or achieving the right things.

Simply put, what we attribute our good feelings to will determine what we do and where we go to get more of them:

- If I think my well-being comes from being around a particular person, I’ll do all sorts of things I wouldn’t otherwise do and put up with things I wouldn’t otherwise put up with in order to keep that person around.

- If I think my well-being comes from my work or my income, then I’ll overinvest in that job and even be willing to ignore my common sense and wisdom in order to preserve or enhance it.

- If I think my well-being comes from a food or drug, I’ll do whatever it takes to get hold of that food or drug the next time I’m feeling in need of another “hit” of good feelings.

Because of the nature of Thought, whatever I continue to think will continue to appear to be real. Our world is what we think it is, and when we think that any of these things will make us happier, they will— at least for a time.

But when you begin to understand that well-being is your nature, not a goal to be pursued, you’ll quickly realize that all you have to do to get it back is to allow your head to clear and Consciousness to wake you back up to who and what you really are.

With all my love,

![]()